A trait that is found among Jews, which is actually essential to their existence, is a high degree of stubbornness.

From this we may understand that every Jew who did not have the ability to cling—stubbornly, steadfastly, ceaselessly—to his identity, his faith, the structural pattern of his life, would not have had the ability to continue to exist, or at least to continue existing as a Jew.

This stubbornness is part of the structural makeup, the essential nature, of the Jew.

In principle, it is this obduracy—“for it is a stiff-necked people” (Exodus, 32:9, 34:9; Deuteronomy 9:13, 10:16)—that is the basis for the hold on the very essence of being a Jew, of remaining a Jew, and, in another sense, of remaining alive at all.

However, like all other character traits, it does not confine itself only to the sphere of beliefs and opinions, but pervades all other aspects of the mind and of life.

So a person whose stubbornness and persistence are no longer directed at maintaining Judaism still retains these qualities but directs them to other aims—either to business and material success, or to intellectual enterprises and so on.

A related Jewish trait, which also derives from both external and internal factors of choice, is a high degree of individualism.

Jewish individualism also stems from the inner culture, since despite all the religious duties that are national, public, and communal, the main spiritual and religious duties of a Jew are essentially linked to his individual nature.

Although Jewish religious life is always centered on a core community, and it is very difficult to maintain a fully satisfying life without the necessary organized support of the community (the minyan), the actual existence of Jewish life does not depend on others.

For example, a Jew does not need—or at least is not required—to conduct his prayers specifically in the synagogue, just as he does not need the services of a priest, since most of his duties are between him and God alone.

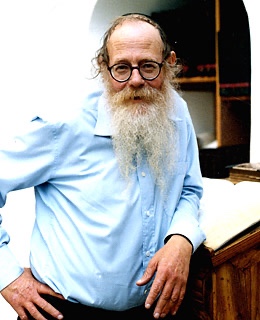

–Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz