From its very beginning, halachah has been connected with differences of opinion, some of which created divisions between Sages and even between groups of Jews.

However, despite all the disputes, and although dispute is a recognized component of Halachah, there has always been a considerable amount of unity within Jewish law, and the same applies to principles of faith.

The principles of Jewish faith were formulated in a relatively late period (the most widely accepted formulation was by Maimonides at the end of the 12th century CE), though many sages to this day have been against formulating principles of faith of any kind.

It is equally true that these principles of faith never had the binding authority of a “credo”; in fact, it is even unclear who wrote the 13 Maimonidean principles of faith printed in most prayer books.

Still, an analysis of the various Jewish sources shows that the principles of our faith are quite unified in terms of worldview and axioms.

Examining even the most profound differences of opinion with the benefit of hindsight leaves one amazed as to how few there are.

This fundamental unanimity exists not because there is some central authority that decides what is permitted, what is forbidden, or what is true faith.

Rather, it is the result of the universal acknowledgment of a corpus of sources, and the acceptance of well-defined methods of interpreting and elaborating those sources.

Accepting the Torah as the foundation, and the Halachic Midrash as the only legitimate way of interpreting it, makes major differences between exegetical conclusions practically impossible, even when different parties try to emphasize those differences.

The disputes between the House of Shammai and the House of Hillel – or, in a late:period, between Hassidim and Mitnagdim – cannot be more than disputes about detail, or semantics.

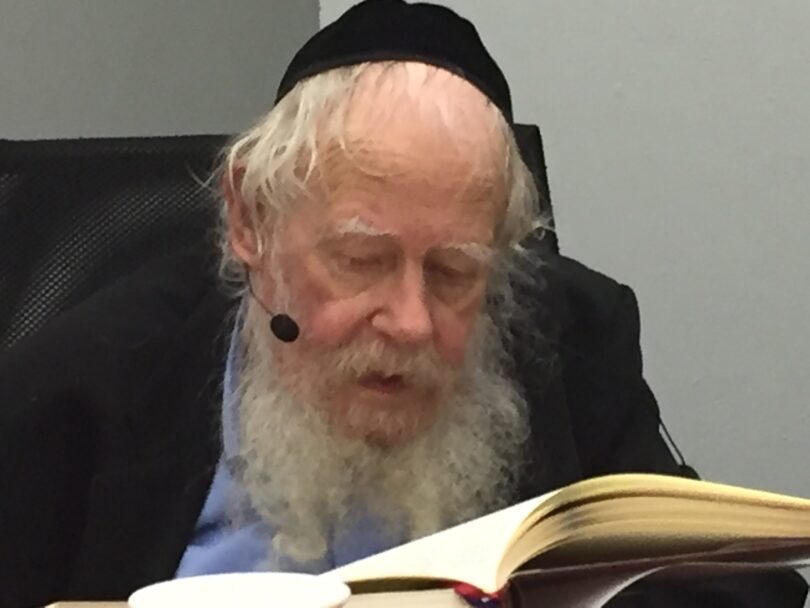

–Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz