The very transition to a life of Torah and mitzvot requires a momentous, fateful decision, but ultimately such a life provides, in certain respects, a great deal of calm.

To put it more profoundly: A world where God exists is a world of peace of mind and security.

A world where God does not exist is a world that is fraught with anxiety and insecurity; it is like an endless maze.

When we speak of the tranquility of a world of Torah and mitzvot, we must ask if this tranquility, while certainly making for a clearer and more orderly world, truly makes for a better world.

It does appear to be a more complete world than the world that is devoid of Torah, but is it truly more complete, or does it just appear to be so?

The answer to this question is that “tzaddikim have no rest.”

Although it is possible to view this lack of rest as secondary, we see that, according to our sages, there is no rest in the World to Come either.

Apparently, lack of rest is an integral and fundamental part of being a tzaddik, perhaps even an ideal form of existence.

Anyone who is a part of the world of faith knows that it is not an easy world in which to live.

Anguish and inner struggle are par for the course for the faithful. It has been said that the verse, “Seven times a tzaddik falls and gets up” (Prov. 24:16), is not a description of the tzaddik’s failures but of his natural progression.

A sharper formulation would be that crisis is part of the process of the tzaddik’s revitalization and rejuvenation, and falling is part of the process of his growth.

Somewhat similarly, the Talmud states that “one does not fully understand the words of the Torah unless he has been tripped up over them” (Gittin 43a).

The simple meaning of this is that, by its very nature, Torah study requires rising and falling; failure is part of the process.

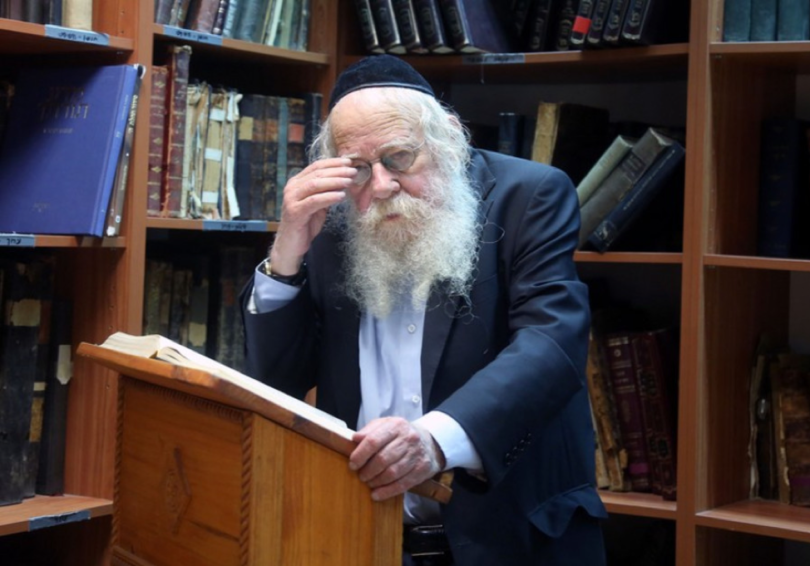

–Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz