We read in Psalms that “a heart broken and crushed, O Lord, You will not scorn” (51:19).

What is the relation between the “crushed and mangled” – of which it says “you shall not do thus in your land” – and “a heart broken and crushed”?

A broken heart is a persons self-evaluation, in relation to others and in relation to God, and the result is the feeling that there is still much to accomplish.

The opposite of a broken heart is what is called “obtuseness of the heart,” as in the verse, “You grew fat, thick, and gross” (Deut. 32:15).

It is the feeling of self-satisfaction, that everything is okay in one’s life.

“Crushed and mangled” is someone who suppresses his drives – and along with them his ambition and creativity – which sometimes happens because of misplaced piety.

Early Christian monks would often castrate themselves for this same reason – the desire to achieve holiness.

Instead of struggling with one’s evil inclination – a protracted struggle that can continue for years, in which one can never be certain that he is truly rid of the inclination – one simply removes the inclination entirely.

One would think that this should be considered an exemplary act.

It is certainly good-intentioned behavior.

To be sure, there are inclinations that cannot be so easily cut off.

Jealousy and honor, for example, are traits that cannot be eliminated from a person’s consciousness.

But if a safe, minor operation can solve the problem of sexual temptation forever, it would seem like the perfect solution to this problem.

Here, however, the verse teaches us not only that if a korban is bruised or crushed, it is then unfit to be brought before the King inside the Temple, but also that this approach should be taken in all areas of spiritual life.

Many baalei teshuva face this very problem.

They observe that since they have become observant, they have lost all of their creativity.

When they were sinners, whether big or small, they were full of vitality and creativity.

Afterward, when they accepted upon themselves the yoke of God’s kingship, they became truly “crushed and mangled, torn and cut,” with all the accompanying ramifications.

They may have a much less powerful evil inclination, but they have rendered themselves impotent in terms of creating good in the world.

When a brilliant mathematician, artist, or writer decides to apply his mind to Torah study, we hope that he maintains his ability to produce wonderful things, as he did in the past.

But if he adopts the religious attitude of being “crushed and mangled,” his brilliance amounts to nothing.

He becomes a kind of insignificant, lowly creature who wanders through the alleyways.

This is true not only of baalei teshuva, but also of those who merely decide to fill their hearts with pure religious devotion.

They often begin to act crushed and stooped, small and broken.

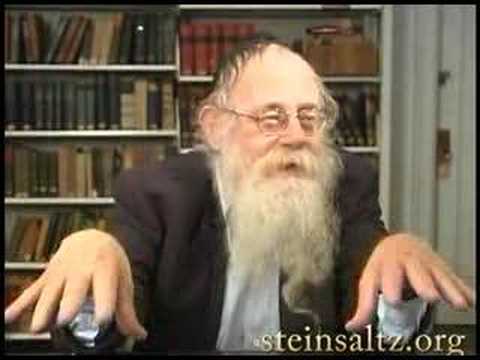

–Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz