As long as we are speaking about different camps – even about rival ones that literally throw stones at each other – we are speaking of normal national existence.

Jews have always lived with controversies.

Psychologically and sociologically speaking – and this also has a sound theological basis – Jews behave as a family, and in a family, siblings always fight with and beat each other, often till they bleed.

Does this mean they cease to be siblings?

Not at all; such fights are part and parcel of the family entity.

Families survive because of the overriding closeness among their members.

Because family members are so close to, as well as in such close proximity with, each other, they often fight.

Thus differences of opinion are not a theoretical matter, but rather lead to discord and even violence.

All the world’s creatures wage their fiercest wars against members of their own kind; it is so with ants, cats, wolves, even moose.

Is this an idyllic picture? Possibly not.

But even the prophet Isaiah, who promised that “the wolf shall dwell with the lamb” (11:6), never promised that two lambs will be able to coexist peacefully.

Yet however unpleasant or even dangerous this may be, it is still within the norm.

Quite often, though, our internal fighting slides toward a point which I find both dangerous and frightening.

I am not making this up.

I have seen such statements in newspapers, and even heard them from individuals – not all extremists – from all walks of Jewish society.

Everyone – those with the earlocks and those who go bare-headed – speak in exactly the same manner about the others.

They say, “What have I got to do with them? We have nothing in common.”

I have heard people make statements such as: Nothing in the world ties me to those religious people; I feel much closer to the Arabs” – along with parallel statements from the other side: “Those secularists, they are just like the gentiles.”

Similarly, “settlers” and “left-wingers” may consider each other total strangers.

Such statements express a kind of acceptance, but a very threatening one.

It is the same kind of acceptance that comes after the death of an enemy;:

I cease to fight because there is no one to fight with anymore.

The other party has changed to such an extent that he has become a stranger.

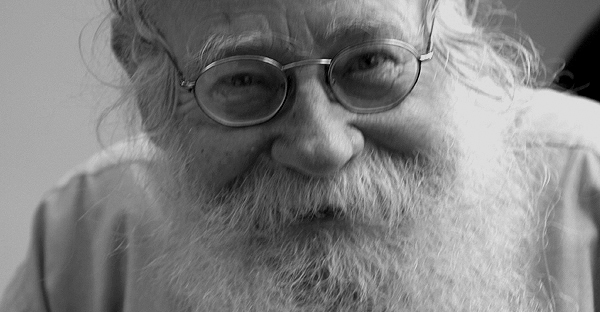

–Rabi Adin Steinsaltz