An examination of the verses in the Torah dealing with Yom Kippur reveals that it includes two motifs.

In Parashat Emor, amidst the descriptions of all the holidays, we find one aspect of Yom Kippur: “It is a Day of Atonement, on which atonement is made on your behalf before God your Lord.”

Yom Kippur is a day of fasting and expiation.

The second motif appears in Parashat Aharei Mot.

There, atonement is also mentioned, but the parasha principally deals with the Service in the Sanctuary, climaxing with the High Priest’s entry into the innermost chamber of the Temple, the Kodesh HaKodashim.

In terms of its character as a day of fasting and atonement, Yom Kippur is a day of complete passivity.

Refraining from work and eating are not forms of activity that bring about atonement; they are the very opposite – forms of refraining from activity.

Regarding atonement, man’s actions are certainly not the decisive factor, but rather, “the essence of the day effects atonement.”

By contrast, in terms of the day’s Service in the Sanctuary, Yom Kippur is filled with activity.

There is no day whose activities are more numerous and complex than those of Yom Kippur.

The preparation and purification of the High Priest, followed by his entry into the Holy of Holies, distinguish the day not only as Yom HaKippurim but also as HaYom HaKadosh (“the Holy Day”).

Thus, the principal and central element of the day is one specific and defined point – atonement – which is flanked by two other elements: confession and teshuva on the one hand and the holy Service in the Sanctuary on the other.

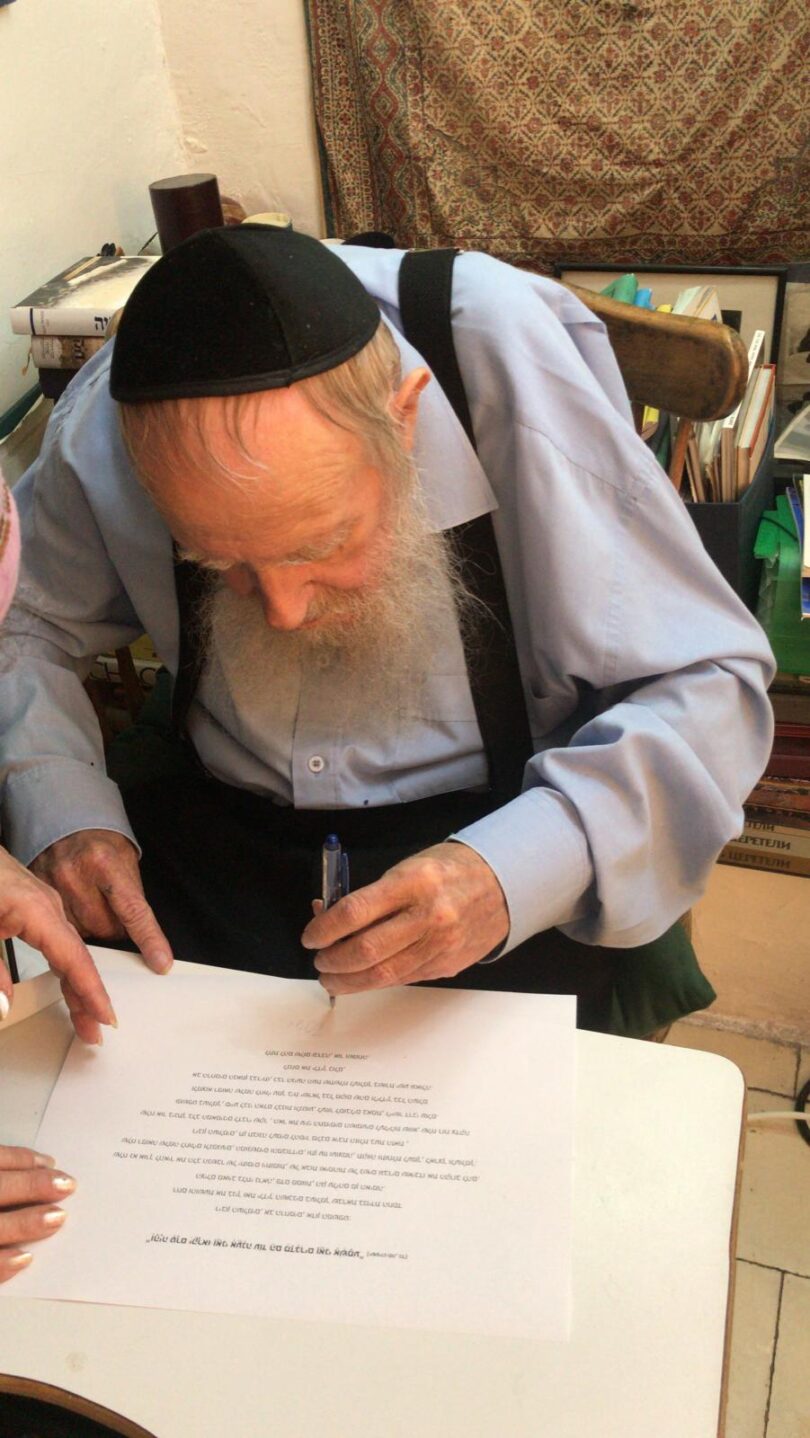

–Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz