Contrary to popular convention, it is not the wonderful in an event that determines its “miraculousness” but the value and significance that that event holds for us.

A given occurrence can be most wondrous and still not be considered a miracle, but merely a natural “curiosity.”

The fact that somewhere out there in a barren wilderness, a stone has rolled to the foot of a mountain, remaining upright all the while, is strange and astonishing, a wonder in itself.

In the absence of significance, however, it is not a miracle.

On the other hand, a perfectly natural occurrence can, under certain circumstances, be considered a miracle because of its significance to the human condition.

An outstanding example of such a “natural” miracle may be found in the biblical story of Esther.

Although the sequence of events described therein proceeds with an inner causality that explains the motivation and actions of each protagonist, it is the historical and personal significance of events that lends this very sequence its miraculous nature.

In the same way, one can, to a great extent, measure the moral value of an action—or an omission.

It is not the deed that determines value so much as the intent on the part of its perpetrator.

The same physical action may be performed legitimately or illicitly, willingly or by coercion, knowingly or in ignorance, accidentally or wantonly, with good intentions or maliciously.

In every evaluation of a deed as good or evil, it is the underlying attitude that determines significance in each case.

Let us say that even where circumstances dictate a given action, the choice of how to relate to that action is free, and its significance follows accordingly.

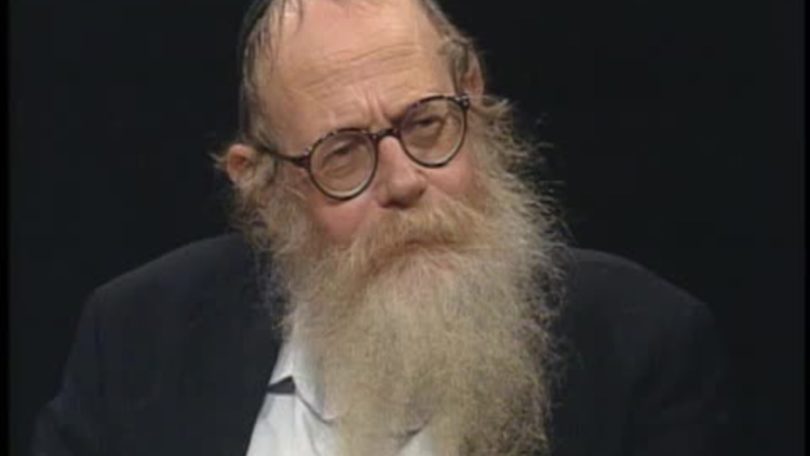

–Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz