The ability to rejoice, to contemplate, or to mourn by the calendar derives from inner discipline, which is an integral part of religious life and one of the decisive elements in the very constitution of a religious person.

Even the most superficial observance of mitzvot requires a high degree of internalization, appreciation, and acceptance.

External pressure to conform is insufficient.

One needs inner strength to perform mitzvot in general, as well as to keep them regularly, in various situations and states of mind.

The observant Jew derives such strength from an inner commitment to certain values, which is termed the “yoke of God’s kingship” or “the yoke of the mitzvot.”

Only by virtue of this commitment can he act the way he does.

Obviously, the depth of this value-oriented attitude differs from one person to the next.

However, even when an individual’s religiosity is a religion of rote, he possesses the capacity to live according to his inner consciousness, no matter how weak and undeveloped it may be.

Such individuals may well be the product of an indoctrinating education, of ignorance, or of spiritual cowardice; they may have no understanding whatsoever of the significance of what they affirm and practice.

Nevertheless, the very fact that they are “religious” – namely, people who observe the commandments – attests to the fact that they do have an inner life, a life determined by values.

All this may seem self-evident, and the emphasis upon it therefore unnecessary.

In today’s world, however, because of many historical and cultural factors, the religious individual is not perceived as religious in the full sense of the term.

Rather, he is perceived largely as a creature of habit, as a personality fashioned by affiliation with a certain sector of the community.

Precisely for this reason, it is important to note that there must be a spiritual, inner component that allows for the existence of such a life.

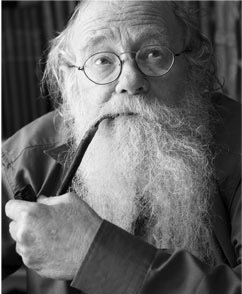

–Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz