A certain tzaddik is reported to have said, “When I think of repentance, I do not deal primarily with the sins that I committed, for in their case I know that they are sins.

Rather, my primary concern is to review the mitzvot that I performed, for in their case there is room for scrutiny and concern.”

Soul-searching, then, is much more than a simple accounting of profit and loss.

Regardless of the kind of problem it deals with – moral, economic, or political – it is an overall reckoning, one that includes a presupposition of the possibility of a major, fundamental mistake.

There is a well-known fable about animals who decide to repent because their sins have brought disaster upon them.

The wolf and the tiger confess that they prey on other creatures, and they are vindicated.

After all, it is in their nature as predators to hunt and kill.

All the animals confess their sins in turn, and all of them, for one reason or another, are exonerated.

Finally, the sheep admits that she once ate the straw lining of her masters boots; here, at last, is obviously the true cause of their suffering.

All the animals fall upon the wicked sheep and devour it, and everything is in order again.

On the surface, the main point of this fable is to condemn the hypocrisy of people who ignore the sins of the strong and harp on those of the weak.

Beyond this, however, there is a more basic and profound message.

The animals conducted an accounting that assumes that the general situation may remain as it is.

The wolf may keep on hunting, and the tiger may continue preying upon others.

If this is the fundamental assumption, then the sin singled out for correction will always be trivial and no real change will be forthcoming.

True soul-searching is based on quite a different premise, one that assumes that the matters that we take for granted, the status quo and the general consensus, are the very things that require re-examination and reassessment.

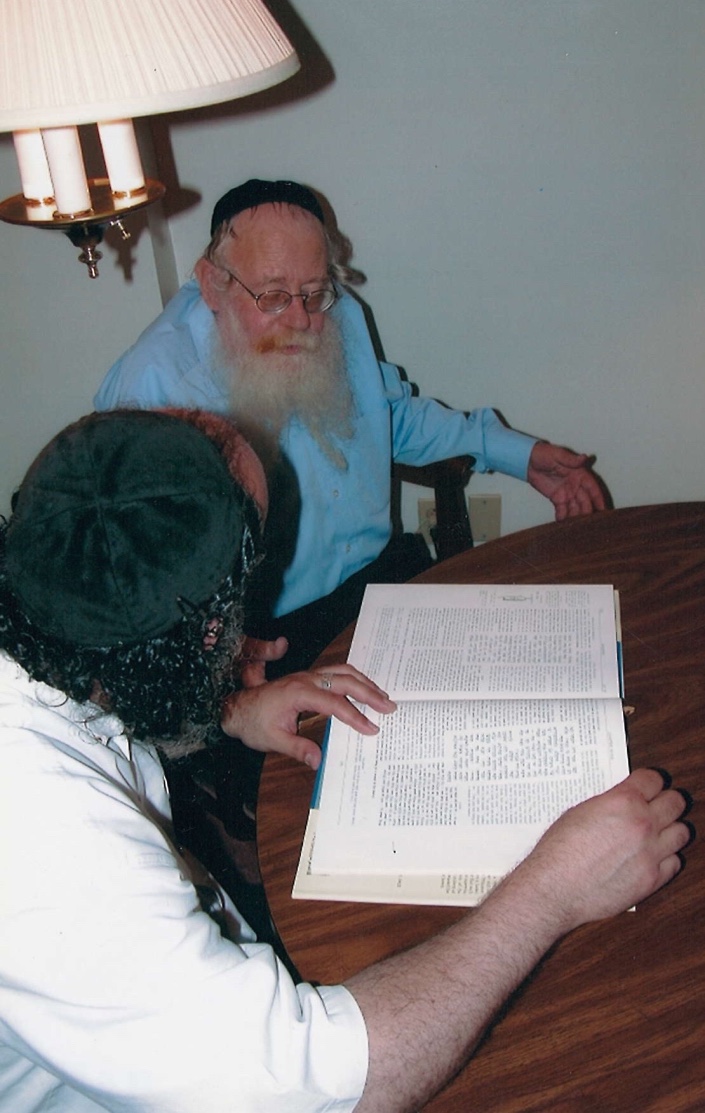

–Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz