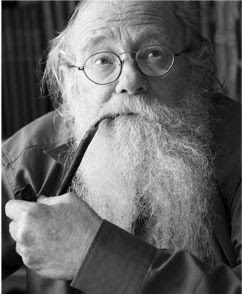

Recently, I heard Rabbi Steinsaltz say that while some people are accident-prone, he himself seems to be “story-prone.” A lot of untrue stories appartently circulate about Rabbi Steinsaltz.

Yesterday, the Executive Editor of Jossey-Bass, one of Rabbi Steinsaltz’s publishers, was talking with me about some of the many articles about Rabbi Steinsaltz frequently appearing in the press.

The conversation prompted me to go back and reread one of my favorite pieces, written by my friend (for over thirty years) Helen Weiss Pincus. Helen received an award from the Society of Professional Journalists for this article (First Place, “Weekly Profile Writing” 2004).

It was called “The World According to Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz.” Here is a slightly edited version of the piece. I hope you enjoy it as much as I do.

Click here:

“The World According to Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz”

By Helen Weiss Pincus, from The New Jersey Jewish Standard, October 31, 2003

Talking with Jerusalem scholar, educator, and author Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz is like grappling with a page of Talmud — a particularly difficult page — full of apparent non-sequiturs and elliptical references. What really interests the rabbi-rebel-scholar-mystic are the world’s “whys.” He eschews answers in favor of questions.

“Unluckily I don’t know enough,” he said in a recent interview. “If I am going to be interviewed I will know even less. When you give all the time answers you don’t have time for questions and the real things are questions. The world is so full of questions. In our times, in a certain way, physics became kind of a shambles. So it is even more interesting because you don’t really know. You know now less than you knew when I was a youngster. You know more but you understand less.”In quest of questions, Rabbi Steinsaltz encourages Talmud study.

.

The culture-spanning image of a pale yeshiva student bent over dusty ancient tomes avidly pursuing pure knowledge – Torah lishma – is as real as ever, but Steinsaltz hopes to extend the exploration of the Talmud to many more people.

In 1965, he founded the Israel Institute for Talmudic Publications, and since then has been working on translating and reinterpreting the Talmud. Thirty-six volumes have been published in Hebrew, and volumes are available in English, French, and Russian.

The Talmud is an extensive amalgam of thousands of years and millions of words of discussions, debates, interpretations, anecdotes, and commentaries on the more succinctly written Chumash — five Books of Moses. While the words, stories, and principles of the Chumash have become woven into other religions, the Talmud remains uniquely Jewish.

Steinsaltz believes Talmud study is the key to Jewish continuity. “A Jewish society that ceases to study the Talmud has no real hope of survival,” Steinsaltz says.

An educational innovator who has established schools on his home turf and abroad, and who at 24, was the youngest school principal in Israel, Rabbi Steinsaltz recalls his own unconventional early educational experiences with nostalgic satisfaction.

“When I entered high school, they began to talk about how a person is supposed to learn something in school. That seemed to me so impossible that I just left.”

Ultimately completing high school in two nonconsecutive years, the unconventional but enthusiastic student filled his open-classroom days by “talking with friends. Being alone. In fact even looking at some of the textbooks of school. I studied mostly Jewish things. It was a very nice time. I was mostly in the street. I learned a lot about Jerusalem, talked with people. I was in places. Not in school. All of it was very helpful.”

Although he clearly relishes his bad-boy past, students applying to Mekor Chaim, the elementary-through-high school yeshiva he founded started in Israel, are put through rigorous testing to filter out all but the “best kind of kids socially, intellectually, and religiously. Anybody that is below a certain level is not accepted. And then we take the best motivated and the best mannered of them.”

The Mekor Chaim teachers are also held to a high standard. In a heterogeneous classroom “a fair amount of kids don’t understand a word. Some of them are not interested and so on. So then if the teacher achieves something, anything, it is an achievement. [But] when you have such a collection, if you don’t achieve, then it shows that somebody is very guilty. If a teacher is not successful with [the Mekor Chaim students] he should be kicked from here to wherever.”

Steinsaltz, as a student, did not harbor such great expectations from his teachers. “In school, you see, I was very quiet. There was a tacit agreement between the school and me. I don’t bother them; they don’t bother me. I was sitting in the last bench. I was shortsighted even then so I didn’t see anything written on the blackboard. But nobody asked me about it. So I was sitting reading books or writing something. I didn’t bother the teachers; the teachers didn’t bother me. It was quiet.”

He acknowledges that despite all available testing a child’s potential sometimes goes undetected. Indeed, he would most likely not have made the cut at Mekor Chaim and the school would have lost a gifted student. “The thing which nobody can find out is who are the children that have the spark. This spark is something that sometimes you see. Something is burning. You know it is there. [But] sometimes it’s so very well hidden … that you don’t see it in them. You don’t see their future abilities or their future potential. I don’t know the way to find it. Maybe it’s the child that gets thrown out of yeshiva. Maybe it’s the child that everyone wants in yeshiva. I don’t know.”

A Guide to Jewish Prayer is one of Steinsaltz’s more than sixty published books. He has spoken to Torah educators about how to make daily prayers meaningful. Could he offer suggestions for leading reluctant teens to prayer? ”

A teenager is really an obnoxious creature. Somebody wrote that human beings are the only creatures in the world that suffer their adolescents to stay with them. All other animals kick them out. All others. Horses. Elephants. They know that [adolescents] are impossible.”

These emerging adults, he continued, “undergo changes. And these changes are not easy at all. You form new relationships with everybody, including yourself. For some people it is a very difficult time. You have to meet your body again and it’s a very different meeting than you had five years ago. You wake up and you find that you have a new life of dreams and desires.”

The educational component is the determinant, he believes, in how children deal with prayer.

“The question is what harm has been done to them before. If children are not pushed by brute force and if they get to understand what is the nature of prayer it is much easier. But in America you don’t speak about prayer. You speak about repeating words in Hebrew that a boy or girl doesn’t really understand. There is no emotional attachment. Prayer is an emotional intellectual communication with God. If you went to a Presbyterian school you possibly heard something about prayer. But if you went to a Jewish school you only heard about ‘davening.’ Small children shouldn’t be pushed into full-fledged davening.”

Steinsaltz also speaks about to doctors at Israeli h

ospitals about medical ethics. He has a lot to tell them.

“There was a time when the doctors had an uncanny interest in me. I spent lots of time in the hospital making their lives miserable. They liked it when I left. I wasn’t very respectful of the doctors.”

Notwithstanding the aid of a computer — a concession to handwriting so illegible that even he has trouble deciphering “a gimel from a chaf sofi,” — words do not flow effortlessly for this prolific writer.

“One page sometimes takes me a whole day. Writing is for me a difficult job but still I manage to do it by stealing time. From whom can I steal time? From myself, from one thing, from another thing, sometimes from sleep. Sometimes, it’s unforgivable, but sometimes from my wife. Writing takes me an enormous amount of time. But sometimes I look back and I see that I did write some words.”

Discussing how to find and allocate precious moments reminds the rabbi of an anecdote.

“It’s a nice story. I have a friend, an acquaintance really. We met years ago. From the beginning he was strange. I used to meet him in hospitals. He would come to the hospital and play the fiddle. He would go from one room to another, ask people what they wanted and play it on the fiddle. He would play whatever they wanted in that particular room and then go on to the next. Big hospitals have lots of rooms so he would spend the day in the hospital. So I met him off and on. I thought perhaps he was one of those well-meaning people who had gotten into a blind alley in life. Later on, by chance I found out that this person didn’t make a living by playing the fiddle. He was a lawyer. He did practice law but only in the late afternoon. He was a lawyer who spent most of his time playing a fiddle. So what is important? It’s a good question.”

The rabbi mused about whether the lawyer should have used his time to achieve something “higher or nobler? He could possibly have become a judge. But he decided to become a fiddler playing in the rooms of a hospital. What’s more important? People make decisions and these are a matter of sacrifice. This is a real person not a story about a legendary figure, a tzaddik. There is a good chance you can bump into the fellow if you happen to visit a hospital in Jerusalem…What do you want to get from life? Probably not what everybody would suggest is the best choice.”

“Sometimes,” he said, “I tell the children [in my schools] that their job is to make the lives of the teachers miserable by asking them questions and making them study something.”

His own childhood was surrounded by many questions and few answers. “When I tell my children that compared to my parents I am a very open book, they don’t believe me. My father was involved in all kind of secret things. His motto was, as in every secret service, ‘You know only what you need to know.’ The need to know is in the present. Everything with respect to the past that has nothing to do with my life was never told to me. Even now I know very little about my parents’ lives. They didn’t talk. First person singular wasn’t very common there.”

A Midrash about biblical patriarch Abraham relates that his father, Terach, once left him in charge of the family business — an idol shop. Rather than sell the merchandise, Abraham, already a confirmed monotheist, challenged the customers’ beliefs and dissuaded them from purchasing the fresh-out-of-the-kiln deities.

“Jewish history,” Steinsaltz said, “basically begins with a naughty boy who went to his father’s business and asked ‘Who cares about this?’ That’s our history.”